Pollutants in the Haw River have made headlines across the state in the past year, but nowhere is the impact of those pollutants greater than in Chatham County.

This week, we speak with two of the leading voices fighting for a cleaner Haw River — Emily Sutton of the Haw River Assembly and Katie Bryant of Clean Haw River. The discussion below is a follow-up to a recent edition of The Chatcast, the podcast of the News + Record, which can be heard here.

Sutton joined the staff of Haw River Assembly in 2016, managing citizen science projects to be a watchdog against sediment pollution and monitor the tributaries and main stem of the Haw River. As Riverkeeper, she is now leading the fight against pollution in the Haw River on many fronts, including emerging contaminants, Jordan Lake nutrients, and sediment pollution. She grew up paddling rivers in the Midwest, and received a degree in Sustainable Development from Appalachian State University, where she also studied agro-ecology, watershed ecology and outdoor education. She lives near Jordan Lake in Chatham County.

Bryant moved to Pittsboro in the summer of 2011. She is a microbiologist and clean water activist dedicated to combating America’s water crisis.

Her background includes biomedical research and development, and pharmaceutical and personal care quality assurance. She also has experience in academic research on post-industrial waste clean up assessments of streams and tributaries. She hopes to bring her love for science, passion to do good, and her ability to conduct root cause analysis of current water treatment systems and how they are failing us. Her mission is to use this knowledge to exact change at the local, state and federal levels. She and her family live just outside Pittsboro. First of two parts.

EMILY SUTTON: It’s important to know how far we’ve come from where we started. This year is the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act; before this legislation passed, it was common practice to use our rivers and streams as disposal systems for all kinds of waste. Rivers caught fire, fish were toxic, and even here the Haw ran the color of the dye used in textile industries upstream.

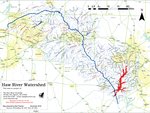

Our watershed is still an industrial one. Reidsville, Greensboro and Burlington each have dozens of industrial facilities producing all kinds of textiles, plastics and various types of manufactured goods. That also means those chemicals used in manufacturing are being discharged into our streams and need to be carefully regulated.

KATIE BRYANT: It’s important for many reasons: when we know how our water is made, we are more likely to appreciate it and protect it — and we need more people to join in this fight. Unfortunately, this must be a grassroots effort to exact change. I feel our local municipal governments and state agencies will not move forward with major changes until our voices get loud.

Additionally, I feel it’s critical for water users to understand the contaminants coming downstream to safeguard themselves and their loved ones. These compounds are in the river and subsequently in our drinking water as the result of industry using chemicals in their manufacturing processes, putting them in their wastewater, the wastewater treatment facility not having the technology to remove the contaminant and then the contaminant passing downstream to Pittsboro’s drinking water plant, which is ill-equipped at removing these volatile organic compounds, and they pass right into the pipes of a Pittsboro home.

The root cause? We don’t use The Precautionary Principle (requiring chemical manufacturers to provide 10 years of data proving the safety of a chemical before use in manufacturing), and we don’t require industry to remove these chemicals out of their waste before sending wastewater to the municipal treatment plant.

I highly encourage everyone throughout the state of North Carolina to get to know their source water and how it’s processed. We need more involvement statewide to protect our natural resources and water users need a voice — the only way this is going to happen is by educating each other and making sure water stays on local and national agendas.

I also want to point out that drinking water from public utilities falls under EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] regulatory standards (whereas bottled water falls under FDA [Food and Drug Administration] standards). This is important to note because achieving better water regulations has turned into a political game — and it starts from the top with how the EPA operates.

The head of the EPA is an appointed position and not a public servant position where you’re chosen by experts in the field. When people are appointed to positions, they run the risk of being let go at any point — so this prevents them from having a voice.

And in my opinion, our political system is highly flawed when it silences experts in any field. North Carolina is not immune to this either — for decades water concerns have been ignored or downplayed and protections have been given to industry and water abusers upstream from Pittsboro. Our state has failed to protect the people and the environment time and time again; they still haven’t revealed the industries responsible for contaminating the Haw and water users have never been issued any guidance from the state regarding our contamination. This should make all of us sit up straight regardless of our political affiliations.

BRYANT: Pittsboro has a history of problems with several contaminants: Trihalomethanes, Bromides, 1,4-Dioxane and PFAS.

Trihalomethanes and Bromides are byproducts of the disinfection process and present in higher concentrations due to the organic matter present within the river. Simply put, when the river water is treated with chlorine, it reacts with organic matter in the river and these byproducts are formed. We don’t hear much about these two contaminants because Pittsboro water utilities have been working to keep these under control due to the EPA disinfection byproduct rule.

1,4-Dioxane is a solvent used in textile processes and PFAS is used in fire retardants, oil, and water repellents, furniture, waterproof clothes, take-out containers, and non-stick cookware. 1,4-Dioxane and PFAS are referred to as emerging contaminants because they aren’t required to be monitored by public utilities. In our case, we found out about the spikes of these contaminants from Dr. Detlef Knappe at N.C. State when his lab sampled our drinking water and presented their findings to the local government, concerned for the health of Pittsboro water users.

It’s critical to note, both 1,4-Dioxane and PFAS are persistent and bioaccumulate, which means they don’t break down easily and gradually increase in concentration within organisms, which is achieved through consuming other contaminated organisms.

Research is showing these contaminants stay within the urban water cycle — as a result it stays within our drinking water, our bodies of water, the air, the rain, and travels into the root system of locally grown foods when watering crops with contaminated water.

The river has an impact on animal species it supports. The fish, the birds, and small and large mammals alike are all at risk of having these contaminants bioaccumulate within them. This has led some states, like Michigan, who are further ahead in their fight against PFAS, to have already started monitoring PFAS in wildlife and issuing “do not eat” warnings.

SUTTON: PFAS and 1,4-Dioxane are industrial contaminants that are known as “forever chemicals.” They are carcinogenic to humans and have been linked to serious health issues, and are not removed in traditional drinking water systems. They are chemically manufactured to never break down. PFAS compounds are found in fire resistant, stain resistant, water resistant, non-stick products.

1,4- Dioxane is a solvent used in industrial manufacturing. We began sampling for these compounds about five years ago, and found that Burlington’s wastewater treatment plant was a primary source of PFAS in the Haw. The wastewater treatment plant accepts industrial waste from users without fully knowing what that wastewater contains. There were no requirements to test for these compounds, so they were not removed.

From our testing, we also discovered that Greensboro was a primary source of 1,4-Dioxane. These compounds are being discharged in high levels from both of these wastewater treatment plants, and our state agencies were doing nothing to regulate the industries and protect communities downstream. We worked with Southern Environmental Law Center to file a Notice of Intent to sue the City of Burlington over their PFAS discharges, and challenged a consent order that would have allowed Greensboro to continue to discharge 1,4-dioxane. Both of those actions have resulted in increased sampling, source tracking, and will lead to minimizing or eliminating the levels of contamination.

SUTTON: The Town of Pittsboro pulls its drinking water directly from the Haw, so these toxins are in that raw source water. Pittsboro has committed to upgrading its water treatment facilities to minimize PFAS levels in their drinking water, but that has not happened yet. These compounds are also found in high levels in land applied biosolids sourced from the wastewater treatment plants, and have a high risk of contaminating groundwater near those application fields.

BRYANT: Research on Pittsboro water users conducted by Duke University revealed a trend with PFAS. It showed if the contaminant is high in the river, it’s high in the sampled population. This is powerful in that it shows how our blood concentrations are directly linked to our drinking water — and drinking these contaminants seems to pose the biggest risk when compared to other routes of exposure.

The health complications associated with the contaminants are shocking: they are linked to cancer risks (prostate, bladder, colon and rectal), rare cancers, endocrine disruption (auto immune disorders), reproductive effects (stillbirths, miscarriages, infertility), and developmental delays, liver and kidney damage, respiratory impairment. The impacts are far and wide, and I highly encourage anyone drinking the water to look into a reverse osmosis system for their kitchen sink.

SUTTON: The Clean Water Act mandates that any discharge into waters must be disclosed in a discharge permit. That federal law is clear, even though our state regulatory agencies have failed to require disclosure on permits. However, the process for regulating how much of something can be discharged is painfully slow. Chemical manufacturers are not required to disclose what their compounds contain, what it is used in, where it is discharged, or what the health risks are of that chemical compound. They are given an “innocent until proven guilty” status.

Once a contaminant is discovered and identified through sampling and analysis, the process for regulating it takes years of health studies and scientific research before it will be considered on the EPA’s “Contaminant Candidate List,” which may or may not lead to regulatory limits in the subsequent years. Meanwhile, communities are being exposed to these toxins every day.

For PFAS, two compounds within that class of 10,000+ have regulatory limits. PFOS and PFOA levels can not exceed 70ug/L, which has been widely criticized for being far too high. Other states are beginning to regulate PFAS with a class approach. This prevents the regulatory “whack-a-mole” for chemical companies; one compound gets regulated and another with a slightly changed chemical composition is put in its place.

For 1,4-Dioxane, we have a numeric limit of 0.35ug/L in water supply watersheds. This regulatory limit needs to be strongly enforced by our state agencies in order to have meaningful protection for communities downstream.

BRYANT: Regarding PFAS, as Emily said, we currently have an EPA health advisory limit of 70 ppt for PFOS and PFOA (only two of the nearly 8000 versions of PFAS). However, that limit is useless since PFOS and PFOA have been phased out of manufacturing. We now have shorter chain PFAS coming downstream to Pittsboro that are showing to pose an even bigger risk to human health.

The EPA has had enough data to make changes in these health advisory limits — and experts agree the limits should reflect the class of compounds, not one or two. For instance, some states are trying to pass a standard of 10 ppt to include all PFAS collectively which is a more reasonable demand considering these compounds are still being used daily in manufacturing. Experts, however, are also arguing 1 ppt collectively should be the max when considering the bioaccumulation — but this is nearly impossible to be adopted into regulation.

We need more protection in Pittsboro. Our water has been used as positive controls in studies here in the state — this is not OK. I am confident as research continues to reveal the impact these compounds are having on towns like Pittsboro; the water users will be able to move forward with legal action. I’ve already started putting my energy into this and hoping to make progress this year.

BRYANT: Clean Haw River is now focusing on creating more conversations between Pittsboro and upstream polluting municipalities. We spoke in December at the Greensboro City Council’s meeting in hopes of creating a relationship and regular communication. Based on the most recent 2021 dumps of 1,4-Dioxane into the Haw River and the lack of enforcement of the Special Order of Consent, we thought it would be beneficial for the council members to see the faces of their neighbors they are sending toxic water to. We plan to keep this momentum and will be speaking soon to Reidsville and Burlington as well.

SUTTON: We are continuing our investigation with the City of Burlington to identify the industrial facilities responsible within that system for the PFAS discharges in order to eliminate that contamination. We are also working to ensure Greensboro meets the monitoring requirements agreed to in our challenge of the Special Order by Consent.

I am working with Riverkeepers across the state to identify potential sources of PFAS: landfills, airports, military bases, wastewater treatment plants and industrial dischargers. We are pushing N.C.’s Department of Environmental Quality to uphold the federal laws laid out in the Clean Water Act and require disclosure, but move beyond that bare minimum requirement to use the analysis done nationwide to move towards a regulatory limit on PFAS as a class.

SUTTON: In the next 10 years, we are going to see exponential growth in this county. This will lead to increases in water use, water discharges and pollution from development. The proposed water allocation transfer from Sanford poses the same risks of contamination that we see now — the levels of PFAS and 1,4-dioxane in Sanford have been even higher than our levels in the Haw. Increasing the quantity of our intake from the Haw could leave the river below adequate flow levels in times of droughts. The expansion to use Jordan Lake as a reservoir is a much safer alternative.

The risks of unchecked development are a major concern for us. Clearing 6,000 acres of forest to build out Chatham Park will result in a significant loss of trees and buffers along streams and the Haw River. Those trees filter out pollutants, slow velocity of runoff and hold in the soil to prevent sedimentation and erosion. We have been monitoring development associated with Chatham Park and have already seen significant sedimentation issues in every major rain event. We have a citizen science program to help us identify sedimentation issues and report them to county officials. I urge community members to take part and help us to keep an eye on development and prevent sedimentation from polluting our streams.

BRYANT: The water will be a concern for some time. This isn’t going away anytime soon. Because these contaminants persist and bioaccumulate, cleaning up and tracking down the contamination will last long after laws and regulations are passed. In addition to identifying our industry polluters, we need to be aware of the following:

1. North Carolina has unlined landfills leaching into waterways (potentially into groundwater) that desperately needs to be addressed.

2. Sludge (biosolids from wastewater treatment) applied to land is running off into the river during rainy seasons and needs to be screened before being land applied.

3. The urban water cycle holds these contaminants within the cycle and are found in the soil, air, and locally grown foods. These too will need to be screened to ensure our safety by the FDA.

4. Improved infrastructure and more advanced treatment technology will be required as new chemicals are used in manufacturing processes — this will be imperative to get ahead of the chemical industry.