North Carolina’s mountains, Piedmont and coast provide more than just gorgeous landscapes and vacation destinations — they contain geological features that have played an important role in the human history of the state and region, as well as fascinating places to explore.

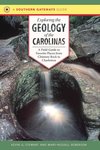

This week, we speak with author Kevin G. Stewart, an associate professor in the Department of Earth, Marine and Environmental Sciences at UNC-Chapel Hill and the co-author, with Mary-Russell Roberson, of “Exploring the Geology of the Carolinas.” The book — subtitled “A Field Guide to Favorite Places from Chimney Rock to Charleston” — is a reader-friendly guide to the geology of North Carolina and South Carolina. It pairs a brief geological history of the region with 31 field trips to easily-accessible (and often familiar) sites in both states where readers can observe firsthand the evidence of geologic change found in rocks, river basins, mountains, waterfalls, and coastal land formations.

Stewart received his Ph.D. from U.C.-Berkeley. His research is focused on the evolution of mountain belts, including the Rocky Mountains of Montana and Wyoming, the Apennines of Italy, and the Appalachians. He’s won numerous teaching awards.

One of the primary goals of our book is to introduce non-geologists to the amazing geologic stories that are contained in the rocks and landscapes of the Carolinas. Geology is everywhere, and in our book we help people “see” geology that they may have been overlooking. Not only has the rich geologic history of the Carolinas created our mountains, piedmont, and coast, but we also show how geology has played an important role in the human history of the Carolinas. Our book gives non-geologists a new way of looking at the history of the Carolinas.

I live in the Piedmont, love to fish at the coast, and enjoy hiking in the mountains but I’d have to say that the Blue Ridge is my favorite. My personal research at UNC-Chapel Hill is focused on the origin of mountains and the Blue Ridge is not only a beautiful part of our state but is also the deeply eroded core of a mountain range that once rivaled the Himalayas in elevation. In the Blue Ridge we can see the inner workings of the mountain building process that is usually deeply buried in other mountain ranges.

When Mary-Russell Roberson and I set out to write our book we wanted to not just describe the geology but to guide people to places where they could see the geology in person. We chose places that contained an interesting geologic story, were easily accessible, and located on public land, mostly in state parks. The hard part was distilling the field trips down to a manageable number. There are many more places we could have included.

Although many people think that Pilot Mountain is an ancient volcano, it’s not. Pilot Mountain stands as a lone peak because it is capped by a layer of rock, called quartzite, that is very resistant to erosion.

The rocky cliffs near the top of Pilot Mountain started as ancient beach sands that were deposited on the shores of the Iapetus Ocean, which is the ocean that existed in this area about 600 million years ago. Eventually these quartz-rich beach sands were buried and metamorphosed into a rock known as quartzite. As the Appalachian Mountains formed, the quartzite and other rocks were uplifted and exposed to erosion. The quartzite was an extensive layer, and parts of it can still be see in Hanging Rock State Park, near Pilot Mountain. The quartzite at Pilot Mountain has been whittled away by erosion leaving the small cap that we see today.

The Rocky Mountains are young, geologically speaking, which is why they stand taller than our old Appalachians, but our mountains are still remarkably high. Mount Mitchell, at 6,684 feet, is the highest point in the U.S. east of the Black Hills in South Dakota. The topographic relief in the Appalachians, which is the difference in elevation between two nearby points, can be as much as a mile, rivaling the topographic relief seen in many places in the Rockies. Despite their antiquity, they are not a dead mountain range. In August 2020, there was a magnitude 5.1 earthquake in the Blue Ridge mountains near Sparta, where the fault broke the surface. This is the first time an earthquake in the eastern U.S. has produced a documented surface rupture.

Chatham County has a wide variety of rock types, including volcanic and sedimentary rocks. The volcanic rocks are over 500 million years old and were erupted from ancient volcanoes that were active when this part of the earth’s crust was part of what is now South America.

Five hundred million years ago, the earth looked very different than it does today and the rocks that make up a significant part of eastern North Carolina were attached to an ancient continent known as Gondwana, which included large parts of present-day South America and Africa. Eventually these pieces of crust detached from Gondwana and, through the magic of plate tectonics, were able to cross the Iapetus Ocean (see Pilot Mountain, above) and collide with ancient North America. These rocks make up most of western and central Chatham County. The low topography in eastern Chatham County is floored by 200-million-year-old sedimentary rocks that fill an ancient rift basin that was created when the continent was pulled apart as the Atlantic Ocean was created. Chatham County has a truly remarkable geologic history!